Foolery, sir, does walk about the orb like the sun. It shines everywhere.

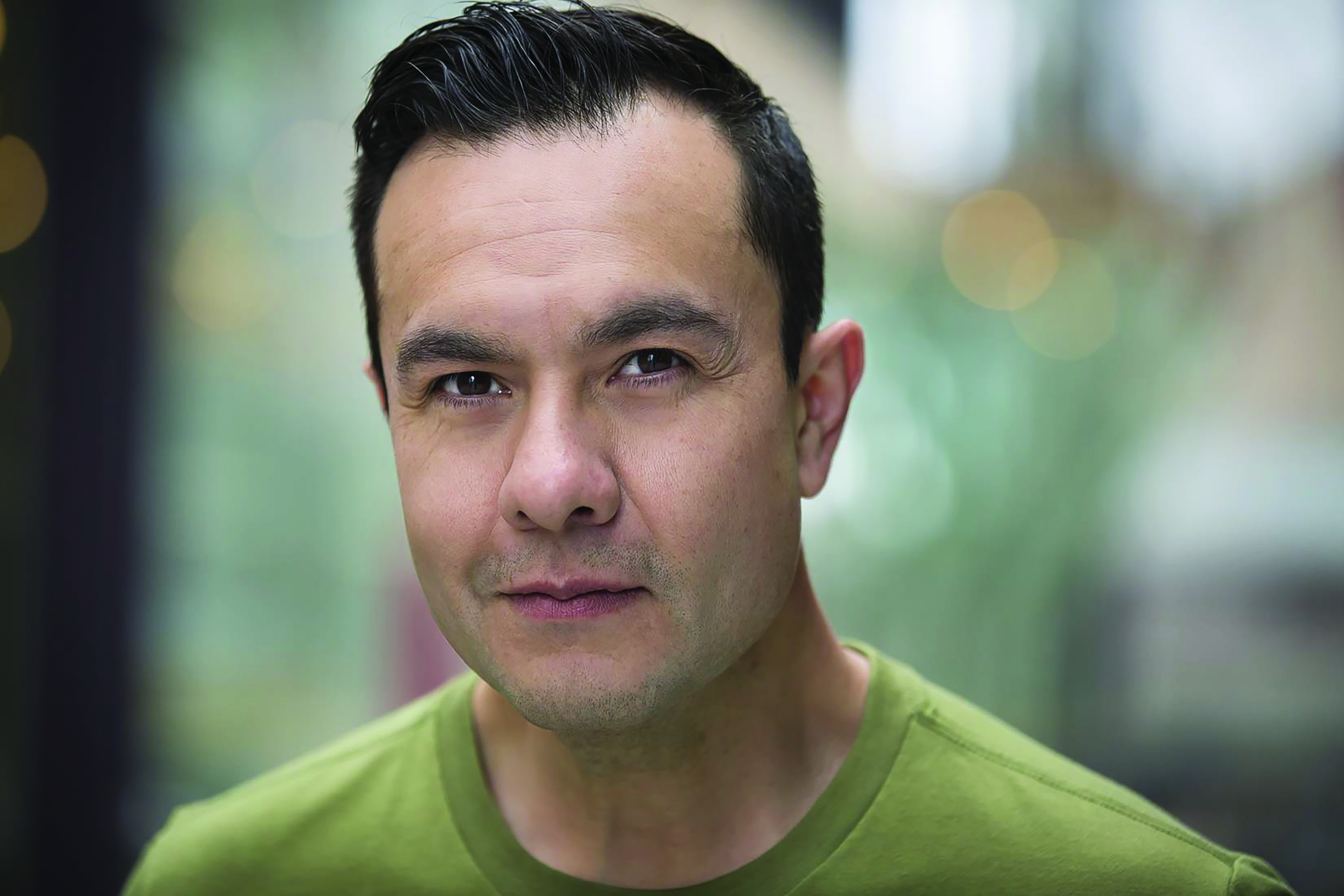

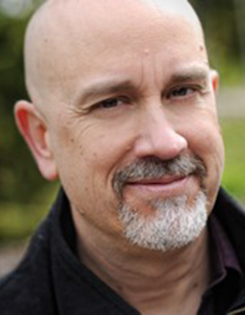

Ring in the summer season with an uproarious comedy about thorny love triangles, mistaken identities … and a pair of twins lost at sea. When Viola finds herself shipwrecked and her brother drowned (or so she thinks!), she begins to dress as a man named Cesario. Meanwhile, her twin Sebastian, very much alive and a near spitting image of Viola/Cesario, also makes his way into town with the help of a friendly outlaw. A night of laugh-out-loud revelry, unexpected romance and original live music from Rinde Eckert follows in this play led by one of the Bard’s most iconic heroines.

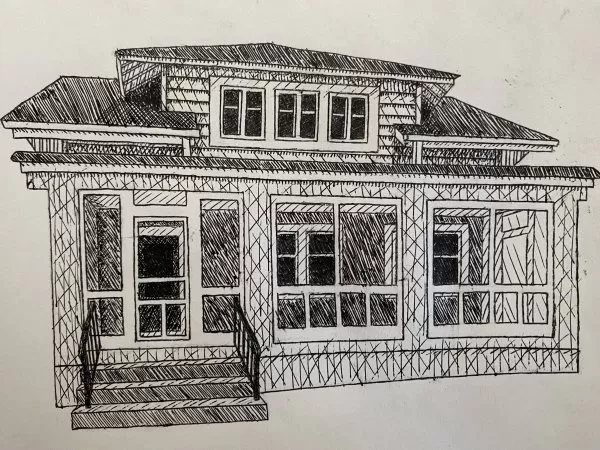

Since 1958, the Colorado Shakespeare Festival has delighted audiences with professional theatre on the CU Boulder campus. Complete your Colorado summer with Shakespeare under the stars in the historic Mary Rippon Outdoor Theatre—complimentary seatbacks included.

Please note:

Attending an outdoor show in the Boulder foothills can be unpredictable. Come prepared to enjoy the adventure by reviewing our weather policy and attire suggestions. Learn more

Performance dates and times:

Sunday, Aug. 11, 7 p.m. SOLD OUT, call the box office at 303-492-8008 for waitlist information.

Buying options

Discounts for groups, youth, seniors, students, active military, CU employees and season ticket orders. Learn more